JFKMLKRFK.com is best viewed on a desktop/laptop, not a cell phone. New layout coming in 2025.

new: MLK holiday Jan. 20, 2025 is inauguration day for the insurrectionist.

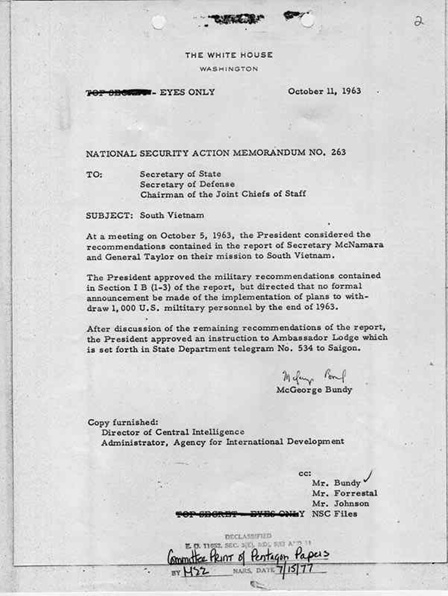

Kennedy's Vietnam withdrawal order: NSAM 263

"Dealey Plaza's crackling rifle fire was directly connected to the scorching of Vietnam flesh by napalm and the millions of deaths our invasion caused."

The JFK Assassination: A False Mystery Concealing State Crimes by Vincent J. Salandria

Coalition on Political Assassinations conference, November 20, 1998

www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/Unspeakable/COPA1998VJS.html

National Security Action Memorandum 263: October 11, 1963

www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/w6LJoSnW4UehkaH9Ip5IAA.aspx

withdrawal discussed at JFK's last press conference

www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Ready-Reference/Press-Conferences/News-Conference-64.aspx

November 14, 1963

QUESTION: Mr. President, in view of the changed situation in South Viet Nam, do you still expect to bring back 1,000 troops before the end of the year, or has that figure been raised or lowered?

THE PRESIDENT: No, we are going to bring back several hundred before the end of the year, but I think on the question of the exact number I thought we would wait until the meeting of November 20th.

October 31, 1963

www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/Press-Conferences/News-Conference-63.aspx

QUESTION: Mr. President, back to the question of troop reductions, are any intended in the Far East at the present time, particularly in Korea, and is there any speed-up in the withdrawal from Viet Nam intended?

THE PRESIDENT: When Secretary McNamara and General Taylor came back, they announced we would expect to withdraw a thousand men from South Viet Nam before the end of the year, and there has been some reference to that by General Harkins. If we are able to do that, that would be our schedule.

One of JFK's last acts was to order the withdrawal of forces from Viet Nam, which LBJ reversed after the coup.

I recommend James Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters, an excellent summary of the 1963 policy shift.

Also recommended is Jim DiEugenio's "Destiny Betrayed" which discusses JFK's 1951 trip to South Viet Nam (and his realization the war against the French was anti-colonial more than pro-communist) and his record in the Senate as the leading champion for decolonialization (read the 1957 speech about Algeria and his support for Congo independence -- a reason Lumumba was killed before JFK became President, and by interesting coincidence it was on the same day as Eisenhower's farewell speech warning of the military industrial complex).

An even better JFK speech, less known, is his September 20, 1963 speech at the UN calling off the nuclear arms race and the moon race, offering instead to convert it to a cooperative effort with the Soviet Union. That got reversed after Dallas, too. If the rocket programs had been merged it would have been harder to plan a war with rockets.

I am grateful that JFK refused to take the advice of the generals in October 1962. He did some evil things getting us into the Missile Crisis but he also did the right thing getting us out of it, and his refusal to bomb Cuba prevented nuclear war. Krushchev deserves some credit, too, for both making an enormous mistake but then realizing that we were all in Noah's Ark together (from his secret correspondence with JFK) and the important thing was to ensure the boat stayed afloat.

He declined multiple opportunities to bomb Cuba, especially during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. When he was removed from office, Castro was meeting with an envoy from the White House (French journalist Jean Daniel) to discuss reopening diplomatic relations, and when they heard the news from Dallas, Castro said this changed everything, as in, there would be no change in US policy now. Castro's speech the next day correctly pointed out that Oswald looked more like an intelligence operative than a communist.

What would America have become if the war on Viet Nam had ended in 1965, the Cold War had also ended in 1965 and the resources wasted on endless conflicts had been directed toward peaceful purposes?

National Security Action Memorandum 263: the withdrawal order

www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/FRUSno194.html

NSAM #263 though very brief, was critical in setting down exactly what President Kennedy had begun to implement with regard to getting the U.S. out of the conflict in Vietnam. Although this Memorandum is short, it directly refers to and builds from the Taylor/McNamara report of October 2, 1963 (document 167 which follows this post) as well as document numbers 179 and 181 (following 167).

NSAM #263 was signed by McGeorge Bundy, JFK's Special Assistant for National Security Affairs. Bundy's role was very heavy in the Kennedy administration in ways JFK, apparently, was not aware of. His signature is also the only one at the bottom of NSAM #273, approved by LBJ just 4 days after JFK was murdered. NSAM #273 was the first evidence of changes in the policies President Kennedy had been putting into place. It did not take long for the new administration to begin to alter JFK's policies, even though LBJ's favorite and most commonly use catch-phrase in the days and months after the assassination--as well as during his own 1964 campaign--was "let us continue," the implication being that Johnson's only interest was in continuing the policies and agendas set forth by his predecessor.

--ratitor

194. National Security Action Memorandum No. 263 [1]

Washington, October 11, 1963.

TO

Secretary of State

Secretary of Defense

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

SUBJECT

South Vietnam

At a meeting on October 5, 1963,[2] the President considered the recommendations contained in the report of Secretary McNamara and General Taylor on their mission to South Vietnam.

The President approved the military recommendations contained in Section I B (1-3) of the report, but directed that no formal announcement be made of the implementation of plans to withdraw 1,000 U.S. military personnel by the end of 1963.

After discussion of the remaining recommendations of the report, the President approved an instruction to Ambassador Lodge which is set forth in State Department telegram No. 534 to Saigon.[3]

McGeorge Bundy

from JFK and the Unspeakable: Why he died and why it matters by James Douglass

about the Kennedy - Morse meeting of November 12, 1963:

Senator Wayne Morse came to the White House to see the president about his education bills. Kennedy wanted to talk instead about Vietnam -- to his most vehement war critic. Morse had been making two to five speeches a week in the Senate against Kennedy on Vietnam. JFK took Morse out into the White House Rose Garden to avoid being overheard or bugged by the CIA.

The president the startled Morse by saying: "Wayne, I want you to know you're absolutely right in your criticism of my Vietnam policy. Keep this in mind. I'm in the midst of an intensive study which substantiates your position on Vietnam. When I'm finished, I want you to give me half a day and come over and analyze it point by point."

Taken aback, Morse asked the president if he understood his objections.

Kennedy said, "If I don't understand your objections by now, I never will."

JFK made sure Morse understood what he was saying. He added, "Wayne, I've decided to get out. Definitely!"

Yet a mind needs hands to carry out its intentions. A president's hands are his staff and extended government bureaucracy. As Kennedy knew, when it came down to the nitty-gritty of carrying out his decision to end the Vietnam War, his administrative hands were resistant to doing what he wanted them to do, especially his Pentagon hands. He also knew that to withdraw from Vietnam "after I win the election" in the fall of 1964, he now had to inspire his aides to continue moving the machinery for withdrawal that he activated on October 11 with National Security Action Memorandum 263."

"After the American University address, John Kennedy and Nikita Krushchev began to act like competitors in peace. They were both turning. However, Kennedy's rejection of Cold War politics was considered treasonous by forces in his own government. In that context, which Kennedy knew well, the American University address was a profile in courage with lethal consequences. President Kennedy's June 10, 1963 call for an end to the Cold War, five and one-half months before his assassination, anticipates Dr. King's courage in his April 4, 1967, Riverside Church address calling for an end to the Vietnam War, exactly one year before his assassination. Each of those transforming speeches was a prophetic statement provoking the reward a prophet traditionally receives. John Kennedy's American University address was to his death in Dallas as Martin Luther King's Riverside Church address was to his death in Memphis."

-- James Douglass "JFK and the Unspeakable: why he died and why it matters"

reviews at: unspeakable.html

Jim Douglass – Confronting the Unspeakable

This section is devoted to the works and words of James W. Douglass

http://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/Unspeakable/

The Hope in Confronting the Unspeakable

in the Assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Keynote Address at The Coalition on Political Assassinations Conference

20 November 2009, Dallas, Texas

http://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/Unspeakable/COPA2009.html

Jim Douglass, author of JFK and The Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters

Delivers the Keynote Address at the Coalition on Political Assassinations Conference

See the video or download (right-click) local copies of: video (mp4) (98 MB), audio (mp3) (63 MB).

General Giap (Vietnamese general fighting the Americans)

his son confirms that the North Vietnam side knew Kennedy was pulling out

https://kennedysandking.com/john-f-kennedy-articles/general-giap-knew

General Giap Knew

By Mani S. Kang

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/52263

The Reflections of JFK's Closest Advisor, Ted Sorensen (Interview)

by Robin Lindley

RL: In your view, Kennedy would not have escalated the US military involvement in Vietnam?

TS: That is definitely my view. In fact, in his last month he was talking about taking out most of the advisors we had there by the end of the year [1963].

RL: Do agree with the conclusion of the Warren Commission that a lone assassin killed Pres. Kennedy?

TS: I examine that question for the first time in my new book, and I conclude that as flawed as the Warren Commission might have been to get a report out in time to calm and quiet the country, there has never been any worthy, credible evidence that would stand up for me as a lawyer in court proving that there was any conspiracy or anyone else behind the lone gunman who turned out to be a lucky sharpshooter.

[it is difficult to believe this was actually his personal view given that the Kennedy family immediately suspected the CIA was involved. It was a political and fear based decision to keep their views private.]

RL: Could you talk about some high points in your international law work?

TS: I worked with Nelson Mandela of South Africa, and helped with something we called the South African Free Election Fund, SAFE, to finance voter education in South Africa because blacks in South Africa had never voted and didn't know the first thing—even about how to mark a ballot. That had a little to do, I believe, with the enormous demonstration of democracy when election day came and voters of all colors turned out for a peaceful, free, fair election that saw Nelson Mandela become president.

That was certainly one of the high points of my international law practice.

RL: Were you involved in the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission?

TS: No, but I know everyone who was. In fact, I'm now on the board of an organization based in this country called the International Commission on Transitional Justice, founded by the people who were the founders and leaders of the commission in South Africa. Transitional justice [concerns] how, after terrible, traumatic conflicts, justice can be restored not only through trials, but also through reconciliation, through open admission that deals with the truth and gets people on both sides of former divisions to accept the truth.

[and now RFK Jr. has joined with others to call for a Truth and Reconciliation effort for the murders of his uncle, President Kennedy, his dad Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.]

www.errolmorris.com/film/fow_transcript.html

from the film "The Fog of War"

Robert McNamara:

October 2nd. I had returned from Vietnam. At that time, we had 16,000 military advisors. I recommended to President Kennedy and the Security Council that we establish a plan and an objective of removing all of them within two years.

October 2nd, 1963

Kennedy: The advantage to taking them out is?

McNamara: We can say to the Congress and people that we do have a plan for reducing the exposure of U.S. combat personnel.

Kennedy: My only reservation about it is if the war doesn't continue to go well, it will look like we were overly optimistic.

McNamara: We need a way to get out of Vietnam, and this is a way of doing it.

Kennedy announced we were going to pull out all of our military advisors by the end of '65 and we were going to take 1000 out by the end of '63 and we did. But, there was a coup in South Vietnam. Diem was overthrown and he and his brother were killed.

I was present with the President when together we received information of that coup. I've never seen him more upset. He totally blanched. President Kenndy and I had tremendous problems with Diem, but my God, he was the authority, he was the head of state. And he was overthrown by a military coup. And Kennedy knew and I knew, that to some degree, the U.S. government was responsible for that. ....

I am inclined to believe that if Kennedy had lived, he would have made a difference. I don't think we would have had 500,000 men there.

www.jfklancer.com/NSAM263.html

www.jfklancer.com/NSAM273.html

www.maryferrell.org/wiki/index.php/1963_Vietnam_Withdrawal_Plans

https://archive.politicalassassinations.net/2013/11/vietnam-and-the-legacy-of-the-jfk-presidency/

Vietnam and the Legacy of the JFK Presidency

November 28, 2013

Kennedy was unequivocally planning to withdraw from Vietnam. Pierre Salinger, his press secretary wrote that he could not understand why people question this since he was told to announce it on the White House steps to the press. The son of John Kenneth Galbraith has written recently about the evidence his father knew as well. Peter Dale Scott and Fletcher Prouty constructed the language of the National Security Action Memoranda that ordered the start of the withdrawal just prior to his death and LBJ’s reversal as soon as he came into office. The State Department released the full text of these documents years ago, just after Stone’s film came out. My mother worked for the Joint Chiefs at the Pentagon as a manpower analyst who projected the national draft call five years in advance, accurate within 100 men. She used percentages derived from experience as well as attrition projections for any given conflict planned. She told me that in April of 1963 for the first time in her career she was told to change her projections on orders of the Kennedy White House and to add in a full withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam by the end of 1964. These were not contingency plan figures, they were implementation projections and had to be right. She told me that his policy was reversed with escalation projections on November 25, 1963, the day of his burial, and she challenged the figures given to her by the Operation and Plans division and the Joint Chiefs. Probably the first civilian protest to the war in Vietnam, because she could not believe the figures. In a full reversal of Kennedy’s policy they told her to project a 10 year war with 57,000 American dead, exactly on target. This false debate about Kennedy’s intentions regarding Vietnam and other liberation struggles against colonial rule in Africa and Central/South America not only obfuscates his intentions, it covers up the intentions for permanent war by those who killed him and why they did. John Judge, Executive Director, COPA

Vietnam and the Legacy of the JFK Presidency

By Paul Jay

The Real News Network

Friday, 22 November 2013 11:12

http://truth-out.org/news/item/20207-vietnam-and-the-legacy-of-the-jfk-presidency-peter-kuznick-on-reality-asserts-itself

TRANSCRIPT:

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself.

November 22 is the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. We’re going to take a look at the significance of his presidency, his accomplishments, and/or lack thereof. And, of course, everything to do with that presidency is a matter of debate. Whether or not President Kennedy actually wanted to pull out of Vietnam or not, and of course the assassination itself, has been the subject of hundreds of books with competing theories. But we’re going to try and take a big-picture look at just what Kennedy represented in terms of the flow of American post-World War II history.

Now joining us to kick off our discussion about Kennedy is Peter Kuznick. He’s a professor of history and director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University. He’s cowriter of the ten-part Showtime series called Untold History of the United States with Oliver Stone.

http://vietnamfulldisclosure.org/index.php/jfk-ordered-full-withdrawal-vietnam-solid-evidence/

This article originally appeared at whowhatwhy.org.

PBS Vietnam Series: Glossing over JFK’s Exit Strategy

By James K. Galbraith

https://whowhatwhy.org/2017/09/26/jfk-ordered-full-withdrawal-vietnam-solid-evidence/

SEPTEMBER 26, 2017 | JAMES K. GALBRAITH

JFK HAD ORDERED FULL WITHDRAWAL FROM VIETNAM: SOLID EVIDENCE

PBS Vietnam Series: Glossing over JFK's Exit Strategy

Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, General Maxwell Taylor and President Kennedy, January 25, 1963. Photo credit: JFK Library

The Ken Burns/Lynn Novick documentary series on Vietnam, currently airing on PBS, skates very lightly over one of the war's most contentious questions: Did John F. Kennedy intend to pursue the fight or to pull out?The second program alludes almost in passing to a withdrawal plan in 1962, conditioned on a then-optimistic assessment of how the war was going. But it also reports Kennedy's qualms, expressed to a friend, as "We don't have a prayer of staying in Vietnam. Those people hate us. They are going to throw our asses out of there at any point. But I can't give up that territory to the communists and get the American people to re-elect me." From this point, the program moves quickly to events in Saigon, to the November 1, 1963 South Vietnamese coup, and to Kennedy's own assassination three weeks later.

But this presentation is highly misleading. In fact, Kennedy's feelings about Vietnam went beyond mere qualms: he had already reached a decision and acted on it. In National Security Action Memorandum 263, dated October 11, 1963, Kennedy articulated his decision to withdraw all US military forces from Vietnam by the end of 1965 — with the withdrawal to be completed after the 1964 election. This was the formal policy of the United States government on the day he died. ...

and two comments posted to whowhatwhy

Kevin Wirsing · September 27, 2017 at 6:13 pm

The issue Prof. Galbraith doesn't discuss and the one that may have upended Kennedy's plans (and to some degree left LBJ in a box): faulty assumptions about the politburo in Hanoi. Burns and Novick do a good job explaining that by August '64, Ho Chi Minh's power was diminished and Le Duan's power was ascending; Duan was very much a hardliner and supporter of the Chinese aggressive attitude…which may well have meant that in 1965 "a face saving" way out may not have been in the cards. Helpful perhaps to remember that although in '65 the Cultural Revolution had not yet really reached its zenith in China, it was heading there; would Duan and his Chinese patrons have countenanced giving the Americans a "face saving" way out?News Nag · October 1, 2017 at 10:19 pm

If that's true, that a hardliner was gaining power in Hanoi, it almost certainly was because JFK was killed in 1963, and to Hanoi's leadership it became very clear that American escalation was going to happen now that Kennedy's decision and legal order were being overturned.Your thought about a withdrawal maybe not having "been in the cards" is a mental contortion that switches effect and cause. That's due to the JFK-Vietnam mythology still being so strong that it contorts thinking around the subject, like light bending due to gravity.

www.bostonreview.net/BR28.5/galbraith.html

Exit Strategy

In 1963, JFK ordered a complete withdrawal from Vietnam

James K. Galbraith

Forty years have passed since November 22, 1963, yet painful mysteries remain. What, at the moment of his death, was John F. Kennedy's policy toward Vietnam?

It's one of the big questions, alternately evaded and disputed over four decades of historical writing. It bears on Kennedy's reputation, of course, though not in an unambiguous way.

And today, larger issues are at stake as the United States faces another indefinite military commitment that might have been avoided and that, perhaps, also cannot be won. The story of Vietnam in 1963 illustrates for us the struggle with policy failure. More deeply, appreciating those distant events tests our capacity as a country to look the reality of our own history in the eye.

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAkennedyJ.htm

(14) Robert S. McNamara interviewed on CNN in June 1996.

The domino theory... was the primary factor motivating the actions of both the Kennedy and the Johnson administrations, without any qualification. It was put forward by President Eisenhower in 1954, very succinctly: If the West loses control of Vietnam, the security of the West will be in danger. "The dominoes will fall," in Eisenhower's words. In a meeting between President Kennedy and President Eisenhower, on January 19, 1961 - the day before President Kennedy's inauguration - the only foreign policy issue fully discussed dealt with Southeast Asia. And there's even today some question as to exactly what Eisenhower said, but it's very clear that a minimum he said... that if necessary, to prevent the loss of Laos, and by implication Vietnam, Eisenhower would be prepared for the U.S. to act unilaterally - to intervene militarily.

And I think that this was fully accepted by President Kennedy and by those of us associated with him. And it was fully accepted by President Johnson when he succeeded as President. The loss of Vietnam would trigger the loss of Southeast Asia, and conceivably even the loss of India, and would strengthen the Chinese and the Soviet position across the world, weakening the security of Western Europe and weakening the security of North America. This was the way we viewed it; I'm not arguing (we viewed it) correctly - don't misunderstand me - but that is the way we viewed it. ...

There were three groups of individuals among his advisers. One group believed that the situation (in South Vietnam) was moving so well that we could make a statement that we'd begin withdrawals and complete them by the end of 1965. Another group believed that the situation wasn't moving that well, but that our mission was solely training and logistics; we'd been there long enough to complete the training, if the South Vietnamese were capable of absorbing it, and if we hadn't proven successful, it's because we were incapable of accomplishing that mission and therefore we were justified in beginning withdrawal. The third group believed we hadn't reached the point where we were justified in withdrawing, and we shouldn't withdraw.

Kennedy listened to the debate, and finally sided with those who believed that either we had succeeded, or were succeeding, and therefore could begin our withdrawal; or alternatively we hadn't succeeded, but that ... we'd been there long enough to test our ability to succeed, and if we weren't succeeding we should begin the withdrawal because it was impossible to accomplish that mission. In any event, he made the decision (to begin withdrawing advisers) that day, and he did announce it. It was highly contested...

Kennedy hadn't said before he died whether, faced with the loss of Vietnam, he would (completely) withdraw; but I believe today that had he faced that choice, he would have withdrawn rather than substitute US combat troops for Vietnamese forces to save South Vietnam. I think he would have concluded that US combat troops could not save Vietnam if Vietnam troops couldn't save it. That was the statement he in effect made publicly before his death, but at that time he hadn't had to choose between losing Vietnam, on the one hand, or putting in US combat troops on the other. Had he faced the decision, I think he would have accepted the loss of Vietnam and refused to put in US combat troops.

(15) Kenneth O'Donnell, Memories of John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1983)

Kennedy had told (Kenneth O'Donnell) in the spring of 1963 that he could not pull out of Vietnam until he was reelected, "So we had better make damned sure I am reelected." ... At a White House reception on Christmas eve, a month after he succeeded to the presidency, Lyndon Johnson told the Joint Chiefs: "Just get me elected, and then you can have your war."

(16) Leroy Fletcher Prouty, The Secret Team (1973)

During those hectic months of late summer in 1963 when the Kennedy Administration appeared to be frustrated and disenchanted with the ten-year regime of Ngo Dinh Diem in Saigon, it approved the plans for the military coup d'état that would overthrow President Diem and get rid of his brother Nhu. The Kennedy Administration gave its support to a cabal of Vietnamese generals who were determined to remove the Ngos from power. Having gone so far as to withdraw its support of the Diem government and to all but openly support the coup, the Administration became impatient with delays and uncertainties from the generals in Saigon, and by late September dispatched General Maxwell D. Taylor, then Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), and Secretary of Defense McNamara to Saigon.

Upon their return, following a brief trip, they submitted a report to President Kennedy, which in proper chronology was the one immediately preceding the remarkable one of December 21, 1963. This earlier report said, among other things "There is no solid evidence of the possibility of a successful coup, although assassination of Diem and Nhu is always a possibility." The latter part of this sentence contained the substantive information. A coup d'état, or assassination is never certain from the point of view of the planners; but whenever United States support of the government in power is withdrawn and a possible coup d'état or assassination is not adamantly opposed, it will happen. Only three days after this report, on October 5, 1963, the White House cabled Ambassador Lodge in Saigon: "There should be... urgent covert effort . . . to identify and build contact with possible alternate leadership." Knowledge of a statement such as this one made by the ostensible defenders and supporters of the Diem regime was all those coup planners needed to know. In less than one month Diem was dead, along with his brother.

Thus, what was considered to be a first prerequisite for a more favorable climate in Vietnam was fulfilled. With the Ngo family out of the way, President Kennedy felt that he had the option to bring the war to a close on his own terms or to continue pressure with covert activities such as had been under way for many years. Because the real authors were well aware of his desires, there was another most important statement in the McNamara-Taylor report of October 2, 1963: "It should be possible to withdraw the bulk of U.S. personnel by that time...." (the end of 1965).

Tuesday, 08 May 2018 17:49

Edmund Gullion, JFK, and the Shaping of a Foreign Policy in Vietnam

Written by James Norwood

www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/john-f-kennedys-vision-of-peace-20131120

John F. Kennedy's Vision of Peace

On the 50th anniversary of JFK's death, his nephew recalls the fallen president's attempts to halt the war machine

By ROBERT F. KENNEDY JR.

November 20, 2013 12:30 PM ET

excerpt:

Today it's fashionable to view the quagmire of Vietnam as a continuum beginning under Eisenhower and steadily escalating through the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon administrations. But JFK was wary of the conflict from the outset and determined to end U.S. involvement at the time of his death.

JFK inherited a deteriorative dilemma. When Eisenhower left office, there were by official count 685 military advisers in Vietnam, sent there to help the government of President Ngo Dinh Diem in its battle against the South Vietnamese guerrillas known as the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese soldiers deployed by Communist ruler Ho Chi Minh, who was intent on reunifying his country. Eisenhower explained that "the loss of South Vietnam would set in motion a crumbling process that could, as it progressed, have grave consequences for us." Ho Chi Minh's popularity in the south had already led Dulles' CIA to sabotage national elections required by the Geneva Accords, which had ended France's colonial rule, and to prop up Diem's crooked puppet government, which was tenuously hanging on to power against the Communists. Back at home, Republican militarists were charging JFK with "losing Laos" and badgering him to ramp up our military commitment.

In JFK's first months in office, the Pentagon asked him to deploy ground troops into Vietnam. JFK agreed to send another 500 advisers, under the assumption that South Vietnam had a large army and would be able to defend itself against communist aggression. He refused to send ground troops but would eventually commit 16,500 advisers – fewer troops than he sent to Mississippi to integrate Ole Miss – who were technically forbidden from engaging in combat missions. He told New York Times columnist Arthur Krock in 1961 that the United States should not involve itself "in civil disturbances created by guerrillas."

For three years, that refusal to send combat troops earned him the antipathy of both liberals and conservatives who rebuked him for "throwing in the towel" in the Cold War. His critics included not just the traditionally bellicose Joint Chiefs and the CIA, but also trusted advisers and friends, including Gen. Maxwell Taylor; Defense Secretary Robert McNamara; McNamara's deputy, Roswell Gilpatric; and Secretary of State Rusk. JFK's ambassador to South Vietnam, Frederick Nolting Jr., reported a "virtually unanimous desire for the introduction of the U.S. forces into Vietnam" by the Vietnamese "in various walks of life." When Vice President Lyndon Johnson visited Vietnam in May 1961, he returned adamant that victory required U.S. combat troops. Virtually every one of JFK's senior staff concurred. Yet JFK resisted. Saigon, he said, would have to fight its own war.

As a stalling tactic, he sent Gen. Taylor to Vietnam on a fact-finding mission in September 1961. Taylor was among my father's best friends. JFK was frank with Taylor – he needed a military man to advise him to get out of Vietnam. According to Taylor, "The last thing he wanted was to put in ground forces. And I knew that." Nevertheless, Taylor was persuaded by hysterical military and intelligence experts across the Pacific, and had angered JFK when he came back recommending U.S. intervention. To prevent the fall of South Vietnam, Taylor suggested sending 8,000 U.S. troops under the guise of "flood relief" – a number that McNamara said was a reasonable start but should be escalated to as many as "six divisions, or about 205,000 men." Later, Taylor would say, "I don't recall anyone who was strongly against [sending troops to Vietnam] except one man, and that was the president."

Frustrated by Taylor's report, JFK then sent a confirmed pacifist, John Kenneth Galbraith, to Vietnam to make the case for nonintervention. But JFK confided his political weakness to Galbraith. "You have to realize," JFK said, "that I can only afford so many defeats in one year." He had the Bay of Pigs and the pulling out of Laos. He couldn't accept a third. Former Vice President Richard Nixon and the CIA's Dulles, whom JFK had fired, were loudly advocating U.S. military intervention in Vietnam, while Asian dominoes tumbled. Even The New York Times agreed. "The present situation," the paper had warned, "is one that brooks no further stalling." This was accepted wisdom among America's leading foreign-policy gurus. Public sympathies in the summer of 1963 were 2-to-1 for intervention.

Despite the drumbeat from the left and right, JFK refused to send in combat troops. "They want a force of American troops," JFK told Schlesinger. "They say it's necessary in order to restore confidence and maintain morale. But it will be just like Berlin. The troops will march in, the bands will play, the crowds will cheer, and in four days everyone will have forgotten. Then we will be told we have to send in more troops. It's like taking a drink. The effect wears off and you have to have another."

In 1967, Daniel Ellsberg interviewed my father. Ellsberg, a wavering war hawk and Marine veteran, was researching the history of the Vietnam War. He had seen the mountains of warmongering memos, advice and pressure. Ellsberg asked my father how JFK had managed to stand against the virtually unanimous tide of pro-war sentiment. My father explained that his brother did not want to follow France into a war of rich against poor, white versus Asian, on the side of imperialism and colonialism against nationalism and self-determination. Pressing my father, Ellsberg asked whether the president would have accepted a South Vietnamese defeat. "We would have handled it like Laos," my father told him. Intrigued, Ellsberg pressed further. "What made him so smart?" Three decades afterward, Ellsberg would vividly recall my father's reaction: "Whap! His hand slapped down on the desk. I jumped in my chair. 'Because we were there!' He slapped the desk again. 'We saw what was happening to the French. We saw it. We were determined never to let that happen to us.'"

In 1951, JFK, then a young congressman, and my father visited Vietnam, where they marveled at the fearlessness of the French Legionnaires and the hopelessness of their cause. On that trip, American diplomat Edmund Gullion warned JFK to avoid the trap. Upon returning, JFK isolated himself with his outspoken opposition to American involvement in this "hopeless internecine struggle."

Three years later, in April 1954, he made himself a pariah within his own party by condemning the Eisenhower administration for entertaining French requests for assistance in Indochina, predicting that fighting Ho Chi Minh would mire the U.S. in France's doomed colonial legacy. "No amount of American military assistance in Indochina can conquer an enemy that is everywhere and at the same time nowhere . . . [or an enemy] which has the sympathy and covert support of the people."

By the summer of 1963, JFK was quietly telling trusted friends and advisers he intended to get out following the 1964 election. These included Rep. Tip O'Neill, McNamara, National Security adviser McGeorge Bundy, Sen. Wayne Morse, Washington columnist Charles Bartlett, Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson, confidant Larry Newman, Gen. Taylor and Marine Commandant Gen. David M. Shoup, who, besides Taylor, was the only other member of the Joint Chiefs that JFK trusted. Both McNamara and Bundy acknowledged in their respective memoirs that JFK meant to get out – which were jarring admissions against self-interest, since these two would remain in the Johnson administration and orchestrate the war's escalation.

That spring, JFK had told Montana Sen. Mike Mansfield, who would become the Vietnam War's most outspoken Senate critic, "I can't do it until 1965, after I'm re-elected." Later that day, he explained to Kenneth O'Donnell, "If I tried to pull out completely from Vietnam, we would have another Joe McCarthy Red scare on our hands, but I can do it after I'm re-elected." Both Nelson Rockefeller and Sen. Barry Goldwater, who were vying to run against him in 1964, were uncompromising Cold Warriors who would have loved to tar JFK with the brush that he had lost not just Laos, but now Vietnam. Goldwater was campaigning on the platform of "bombing Vietnam back into the Stone Age," a lyrical and satisfying construct to the Joint Chiefs and the CIA. "So we had better make damned sure I am re-elected," JFK said.

The Joint Chiefs, already in open revolt against JFK for failing to unleash the dogs of war in Cuba and Laos, were unanimous in urging a massive influx of ground troops and were incensed with talk of withdrawal. The mood in Langley was even uglier. Journalist Richard Starnes, filing from Vietnam, gave a stark assessment in The Washington Daily News of the CIA's unrestrained thirst for power in Vietnam. Starnes quoted high-level U.S. officials horrified by the CIA's role in escalating the conflict. They described an insubordinate, out-of-control agency, which one top official called a "malignancy." He doubted that "even the White House could control it any longer." Another warned, "If the United States ever experiences a [coup], it will come from the CIA and not from the Pentagon." Added another, "[Members of the CIA] represent tremendous power and total unaccountability to anyone."

Defying such pressures, JFK, in the spring of 1962, told McNamara to order the Joint Chiefs to begin planning for a phased withdrawal that would disengage the U.S. altogether. McNamara later told an assistant secretary of defense that the president intended to "close out Vietnam by '65 whether it was in good shape or bad."

On May 8th, 1962, following JFK's orders, McNamara instructed a stunned Gen. Paul Harkins "to devise a plan for bringing full responsibility [for the Vietnam War] over to South Vietnam." Mutinous, the general ignored the order until July 23rd, 1962, when McNamara again commanded him to produce a plan for withdrawal. The brass returned May 6th, 1963, with a half-baked proposal that didn't complete withdrawal as quickly as JFK had wanted. McNamara ordered them back yet again.

On September 2nd, 1963, in a televised interview, JFK told the American people he didn't want to get drawn into Vietnam. "In the final analysis, it is their war," he said. "They are the ones who have to win or lose it. We can help them, we can give them equipment. We can send our men out there as advisers, but they have to win it, the people of Vietnam."

Six weeks before his death, on October 11th, 1963, JFK bypassed his own National Security Council and had Bundy issue National Security Action Memorandum 263, making official policy the withdrawal from Vietnam of the bulk of U.S. military personnel by the end of 1965, beginning with "1,000 U.S. military personnel by the end of 1963." On November 14th, 1963, a week before Dallas, he announced at a press conference that he was ordering up a plan for "how we can bring Americans out of there." The morning of November 21st, as he prepared to leave for Texas, he reviewed a casualty list for Vietnam indicating that more than 100 Americans to date had died there. Shaken and angry, JFK told his assistant press secretary Malcolm Kilduff, "It's time for us to get out. The Vietnamese aren't fighting for themselves. We're the ones doing the fighting. After I come back from Texas, that's going to change. There's no reason for us to lose another man over there. Vietnam is not worth another American life."

On November 24th, 1963, two days after JFK died, Lyndon Johnson met with South Vietnam Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, whom JFK had been on the verge of firing. LBJ told Lodge, "I am not going to lose Vietnam. I am not going to be the president who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went." Over the next decade, nearly 3 million Americans, including many of my friends, would enter the paddies of Vietnam, and 58,000, including my cousin George Skakel, would never return.

Dulles, fired by JFK after the Bay of Pigs, returned to public service when LBJ appointed him to the Warren Commission, where he systematically concealed the agency's involvement in various assassination schemes and its ties to organized crime. To a young writer, he revealed his continued resentment against JFK: "That little Kennedy . . . he thought he was a god."

related websites:

JFKMLKRFK.com - by Mark Robinowitz - updated

January 13, 2025